The Peasants’ Revolt, also named Wat Tyler’s Rebellion or the Great Rising, was a major uprising across large parts of England in 1381. The revolt had various causes, including the socio-economic and political tensions generated by the Black Death in the 1340s, the high taxes resulting from the conflict with France during the Hundred Years’ War and instability within the local leadership of London.

Unpaid poll taxes

The final trigger for the revolt was the intervention of a royal official, John Bampton, in Essex on 30 May 1381. His attempts to collect unpaid poll taxes in Brentwood ended in a violent confrontation, which rapidly spread across the south-east of the country. A wide spectrum of rural society, including many local artisans and village officials, rose up in protest, burning court records and opening the local gaols. The rebels sought a reduction in taxation, an end to the system of unfree labour known as serfdom, and the removal of the King’s senior officials and law courts.

Inspired by the sermons of the radical cleric John Ball and led by Wat Tyler, a contingent of Kentish rebels advanced on London. They were met at Blackheath by representatives of the royal government, who unsuccessfully attempted to persuade them to return home.

London under siege

King Richard II, then aged 14, retreated to the safety of the Tower of London, but most of the royal forces were abroad or in northern England. On 13 June, the rebels entered London and, joined by many local townsfolk, attacked the gaols, destroyed the Savoy Palace, set fire to law books and buildings in the Temple, and killed anyone associated with the royal government.

The following day, Richard met the rebels at Mile End and acceded to most of their demands, including the abolition of serfdom. Meanwhile, rebels entered the Tower of London, killing the Lord Chancellor and the Lord High Treasurer, whom they found inside.

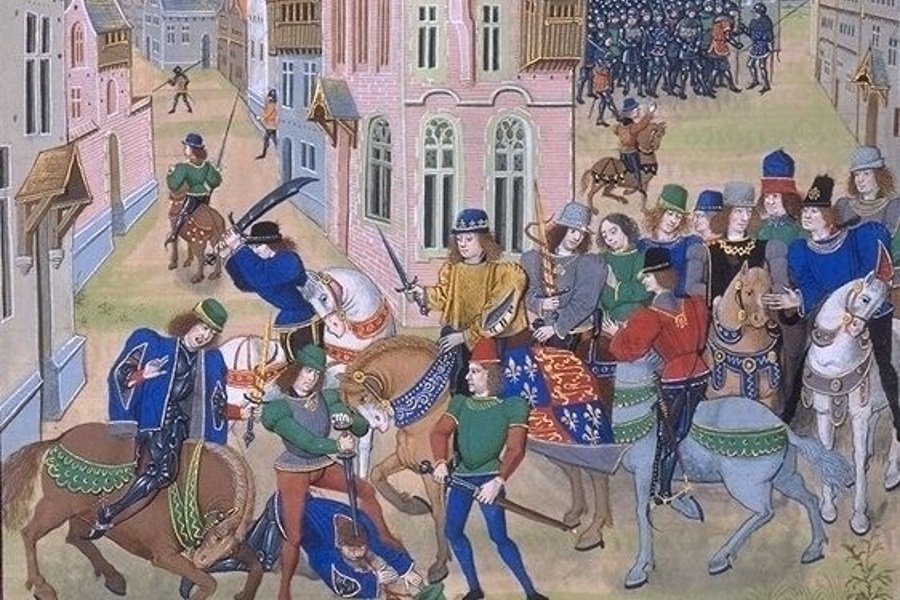

On 15 June, Richard left the city to meet Tyler and the rebels at Smithfield. Violence broke out, and Richard’s party killed Tyler. Richard defused the tense situation long enough for London’s mayor, William Walworth, to gather a militia from the city and disperse the rebel forces.

Order was re-established

Richard immediately began to re-establish order in London and rescinded his previous grants to the rebels. The revolt had also spread into East Anglia, where the University of Cambridge was attacked and many royal officials were killed. Unrest continued until the intervention of Henry Despenser, who defeated a rebel army at the Battle of North Walsham on 25 or 26 June.

Troubles extended north to York, Beverley and Scarborough, and as far west as Bridgwater in Somerset. Richard mobilised 4,000 soldiers to restore order. Most of the rebel leaders were tracked down and executed; by November, at least 1,500 rebels had been killed.

Interpretations of the war

The Peasants’ Revolt has been widely studied by academics. Late 19th-century historians used a range of sources from contemporary chroniclers to assemble an account of the uprising, and these were supplemented in the 20th century by research using court records and local archives.

Interpretations of the revolt have shifted over the years. It was once seen as a defining moment in English history, but modern academics are less certain of its impact on subsequent social and economic history. The revolt heavily influenced the course of the Hundred Years’ War, by deterring later Parliaments from raising additional taxes to pay for military campaigns in France.

The revolt has been widely used in socialist literature, including by the author William Morris, and remains a potent political symbol for the political left, informing the arguments surrounding the introduction of the Community Charge in the United Kingdom during the 1980s.

Author Profile

Latest entries

History20/07/2020The Most Bizarre Things That Was Found In Ice

History20/07/2020The Most Bizarre Things That Was Found In Ice History20/07/2020The Maid of Orléans : How Joan of Arc defeated the English

History20/07/2020The Maid of Orléans : How Joan of Arc defeated the English History03/07/2020Religious Cults That Changed The Course Of History

History03/07/2020Religious Cults That Changed The Course Of History History22/04/2020World War II Stories: Nazis Killed Her Husband, She Bought A Tank And Went On A Rampage

History22/04/2020World War II Stories: Nazis Killed Her Husband, She Bought A Tank And Went On A Rampage